Foreign Income Tax Australia: Your Essential Guide

- Jul 5, 2025

- 15 min read

If you're an Australian resident for tax purposes, the rule is refreshingly simple: you must declare all income you earn, from all sources, worldwide.

It doesn't matter if it's from a job in Sydney or a rental property in London. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) treats all your income—both local and international—as one big pool. This holds true even if you've already paid tax on that income in the country where you earned it.

Getting your head around this core principle is the first and most crucial step to managing your foreign income tax in Australia. If you have overseas earnings, investments, or assets, failing to report them can unfortunately lead to some hefty penalties.

What Counts as Foreign Income in Australia?

Foreign income often stems from overseas work, travel, or investments — make sure it's declared to the ATO if you're an Australian resident for tax purposes.

The term "worldwide income" can sound a bit daunting, but it’s a fundamental part of our tax system. If you're an Australian resident for tax purposes, the ATO needs your tax return to paint a complete picture of your financial life, no matter where in the world it happens.

This rule is all about fairness. It ensures that income earned from a job in London is treated the same as one in Melbourne. The real trigger here is your tax residency status, which we’ll dive into a bit later. For now, the key takeaway is that geography doesn't shield your earnings from Australian tax law if you're a resident.

The Worldwide Income Principle Explained

The idea of taxing worldwide income isn't unique to Australia; it’s a common feature in many developed countries. In fact, Australia's tax system is ranked 13th out of 38 OECD countries for its overall competitiveness, which considers how things like foreign profits are handled.

For you as an individual, this just means you need to be aware of all the different types of income that need to go on your tax return. This includes things like:

Salary or wages from working overseas.

Pensions and annuities from foreign funds.

Interest earned from an overseas bank account.

Dividends and capital gains from foreign shares or investments.

Rental income from a property you own abroad.

The bottom line is this: your tax obligations are tied to you as a resident, not to the location where the money was made. It's a system designed to prevent people from using offshore accounts or investments to sidestep paying their fair share of tax here at home.

To make things even clearer, here's a quick summary of these foundational rules.

Australian Foreign Income Rules at a Glance

This table breaks down the core concepts you need to know about declaring foreign income.

Concept | What It Means for You |

|---|---|

Worldwide Income | As an Australian tax resident, you must report all income earned globally on your Australian tax return. |

Tax Residency | Your status as a "resident for tax purposes" is what determines your obligation to report worldwide income. |

Foreign Tax Paid | Even if you paid tax in another country, you still need to declare the income to the ATO. |

Preventing Double Tax | Don't worry, you can often claim a credit for foreign tax paid to reduce your Australian tax bill, avoiding being taxed twice. |

These principles form the bedrock of Australia's foreign income rules. Understanding them will help you navigate your obligations and ensure you're doing the right thing come tax time.

Determining Your Australian Tax Residency Status

Before you even start thinking about foreign income, there’s a much more fundamental question you need to answer: Are you an Australian resident for tax purposes? This single factor is the linchpin that decides whether you pay tax here on just your Australian income, or on your entire worldwide income. Getting this right is the most critical piece of the puzzle.

The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) doesn't leave this to guesswork. They use four distinct tests to figure out your status. The crucial thing to remember is that you only need to pass one of these tests to be considered a tax resident. It's not a checklist where you have to tick all four boxes; think of them as separate gateways to residency.

The Four Key Residency Tests Explained

The ATO applies these tests in a specific order, kicking off with the main one, known as the "resides test." If your situation is clear-cut under this first test, there's usually no need to look any further. But if it's a bit of a grey area, they'll move down the list to make a final call.

1. The Resides Test: This is the primary and most common-sense test. It simply looks at your overall situation to determine if you "reside" in Australia in the ordinary meaning of the word. The ATO considers things like your physical presence, your intentions, your family and business ties, and where you keep your main assets. If you live in Australia with your family in a permanent home, you’ll almost certainly pass this test.

2. The Domicile Test: If you don't pass the resides test, this one comes into play. Your "domicile" is your legal home—the country the law sees as your permanent base. If your domicile is Australia, you're a tax resident unless the ATO is satisfied that your permanent place of abode is genuinely outside Australia. This often catches Australian citizens who are working overseas temporarily but haven't set up a permanent new home elsewhere.

3. The 183-Day Rule: This one is a straightforward numbers game. If you are physically in Australia for more than half the income year (183 days or more), you’re generally considered a resident. This applies whether those days are all in one block or spread out. The only way out of this is if you can prove your usual home is outside Australia and you have no intention of moving here.

4. The Superannuation Test: This is a very specific test for Australian government employees working overseas. If you're contributing to certain public sector superannuation schemes (like the PSS or CSS), you, your spouse, and your children under 16 are automatically considered Australian residents for tax purposes.

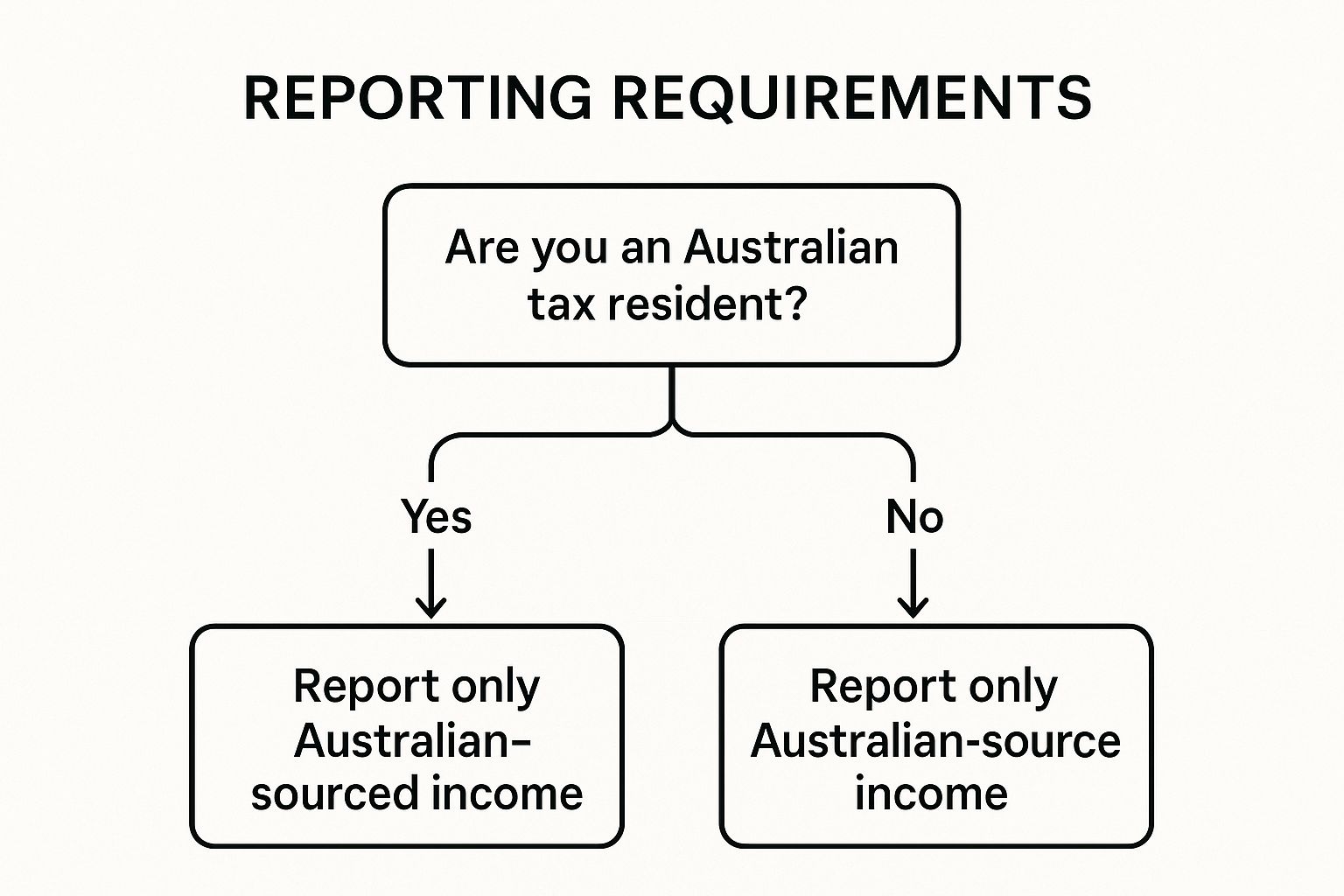

This simple decision tree shows exactly how your tax residency status changes what you need to report.

The takeaway is simple. A "Yes" to Australian tax residency means you must declare all your income from around the globe. A "No" means your tax obligations here are limited to income you earned from Australian sources.

Key Takeaway: Residency isn't just about your citizenship or a simple day count. It's a "whole-of-situation" assessment based on your life, your connections, and your ties to Australia. Nailing this down from the start is the foundation of a correct and stress-free tax return.

Understanding which test applies to you is essential for getting your tax filings right. For a deeper dive into what you need to prepare and lodge, check out our complete guide to the Australian tax return process with the ATO.

What Kinds of Foreign Income Do I Need to Declare?

Tax offsets can reduce the amount of tax you pay — learn which foreign income offsets may apply if you're an Australian resident.

When you hear "foreign income," what pops into your head? For most people, it's a salary from an overseas job. That's a big one, for sure, but it’s really just the tip of the iceberg.

The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) casts a wide net. Their definition of foreign income covers almost any money you earn or profit you make outside of Australia. Knowing what falls under this umbrella is essential for getting your tax return right. A small oversight can cause big headaches later on.

Let's break down the most common types of foreign income you need to have on your radar.

Employment and Business Income

This one is the most straightforward. It covers any salary, wages, bonuses, or director's fees you get from working for an employer based outside Australia. For instance, if you're an Aussie resident on a temporary work assignment in Singapore, your salary from that Singaporean company is foreign income. Simple.

It also includes profits from any business you're running overseas. Let's say you operate a small e-commerce store with customers mostly in the United States, and the business is registered there. The net profit you make is foreign income and has to be declared back home in Australia.

Investments and Dividends

Your global investment portfolio is another major area. Any income your international assets generate needs to be reported, and this is where many people trip up, especially with how easy it is to invest in global markets these days.

Common examples include:

Interest from Foreign Bank Accounts: That bit of interest earned on a savings account you hold with a bank in the UK.

Dividends from International Shares: The dividends you receive from your shares in a US-based giant like Apple or Microsoft.

Distributions from Foreign Trusts: Any payments you get as a beneficiary of a trust that's located and managed overseas.

Important Note: Even if dividends are automatically reinvested and you never see the cash in your bank account, they still count as income for that financial year. You must report them.

Rental and Property Income

Owning property overseas is a fantastic asset, but any money it brings in is taxable right here in Australia. This is a crucial point for expats or anyone who has inherited property abroad.

For example, if you own an apartment in Bali and rent it out to holidaymakers, the net rental profit—after you’ve subtracted all the eligible expenses—must be included in your Australian tax return. This requires diligent record-keeping of both what you earned and what you spent. Many of the same expense principles apply, which you can learn more about in our guide to [tax deductions for rental property](https://www.baronaccounting.com/post/tax-deductions-for-rental-property).

Capital Gains on Foreign Assets

Finally, you can't forget about capital gains. A capital gains event happens whenever you sell, trade, or even give away a foreign asset.

A classic case is selling an investment property in New Zealand that you bought a few years back. The profit you make on that sale is a foreign capital gain, and the ATO needs to know about it. In the same way, selling shares in a foreign company for a profit also triggers a capital gain that must be reported on your Australian tax return.

How Foreign Tax Credits Prevent Double Taxation

One of the biggest fears for anyone earning money overseas is the nightmare of double taxation. The idea of being taxed by a foreign government and then again by the ATO on the very same dollar is a completely valid concern.

Thankfully, the Australian tax system has a built-in safety valve to prevent this: the Foreign Income Tax Offset (FITO).

Think of the FITO as a 'credit' you get for taxes you've already paid elsewhere. For every dollar of tax you pay to a foreign government on your income, you get an equivalent credit to use against your Australian tax bill. This is the cornerstone of making the global income reporting system fair. It ensures that while you must report your worldwide income, you don’t end up paying tax on it twice.

Understanding The FITO Calculation

Now, it's not a completely unlimited, dollar-for-dollar exchange. The amount of offset you can claim is capped. You can claim a credit for the foreign tax you've paid, but only up to the amount of Australian tax you would have been liable for on that same income.

Key Concept: The FITO will reduce your Australian tax payable, but it can't result in a refund on its own. Its purpose is to neutralise double tax, not to pay you back more than the Australian tax you owe on that foreign income.

Let’s look at an example. Imagine you earned $10,000 in foreign income and paid $1,500 in tax to that country. If the Australian tax payable on that same $10,000 would have been $2,000, you can claim the full $1,500 offset. Simple.

However, if the Australian tax was only $1,200, your FITO claim would be capped at $1,200. You can't claim more than what you would have owed in Australia.

What You Need To Claim The Offset

To successfully claim the FITO, meticulous record-keeping is non-negotiable. You must be able to prove to the ATO that you genuinely paid the foreign tax.

Essential documents include:

Foreign tax assessment notices: This is the official document from the foreign tax authority showing your tax liability.

Payslips or income statements: These should clearly show the gross income earned and the foreign tax withheld.

Bank statements: These can provide proof of tax payments made from your account.

It's also useful to see how this fits into the bigger picture. Australia taxes different people differently. For instance, non-residents face a flat tax rate of 30% on their Australian-sourced income up to $135,000 for the 2024/25 and 2025/26 financial years.

Unlike residents, non-residents aren't required to pay the Medicare levy. This detail can significantly affect their overall tax position, which is something residents often need to plan for. You can learn more by understanding the Medicare levy and surcharge in our detailed guide. This system for non-residents is part of a wider government focus on ensuring fair tax contributions from everyone.

Navigating Complex Rules for Investments and Entities

When your money starts crossing borders, Australian tax rules can get a lot more complicated than just declaring wages. Once you get into international investments, overseas business structures, or even unique residency situations, a whole different set of rules kicks in.

Getting your head around these specific regulations is absolutely vital. It’s not just about staying compliant with the ATO; it’s about making smart financial moves. The good news is that the ATO has laid out clear guidelines for these more advanced scenarios, covering everything from overseas companies to capital gains, to make sure all income is handled correctly.

Controlled Foreign Corporations and Anti-Deferral Rules

One of the trickiest areas of foreign income tax in Australia involves what’s known as a Controlled Foreign Corporation, or CFC. Put simply, a CFC is a foreign company that is mostly controlled by Australian residents.

To deal with these, the Australian government has "anti-deferral" rules. These rules are specifically designed to stop Australian residents from using offshore companies to endlessly delay—or "defer"—paying Australian tax on the profits they've earned.

Think of a CFC as a foreign treasure chest that’s controlled by Australians. The anti-deferral rules make sure that certain types of 'passive' income (like interest or some rent) earned and stashed in that chest are still taxed back here in Australia, even if the cash itself hasn't come home yet.

This is a direct measure to prevent profits from being parked in low-tax countries just to sidestep Australian tax. These rules specifically zero in on passive income and other types of income that can be easily shifted around the globe.

Foreign Capital Gains and the CGT Discount

So, what happens when you sell a foreign asset, like shares in a US tech company or an investment property you own in the UK? Just like selling an asset here at home, you might have a capital gain or loss, and you need to report it on your Australian tax return.

A very common question we get is whether the 50% Capital Gains Tax (CGT) discount applies to foreign assets. For individual Australian residents, the answer is usually yes. If you've held onto that foreign asset for more than 12 months, you can typically cut your taxable capital gain in half.

Special Rules for Temporary Residents

The tax system offers a pretty significant break for temporary residents. If you're in Australia on a temporary visa (and neither you nor your spouse is an Australian resident for social security purposes), the rules are much more straightforward.

For the most part, temporary residents only pay tax on their Australian-sourced income. Most of your foreign income is exempt, but there are two main exceptions to watch out for:

Income you earn from employment while you're a temporary resident.

Capital gains you make on certain types of taxable Australian property.

This means that any money you earn from overseas investments or foreign bank accounts is generally not taxed in Australia while you're a temporary resident. This is a sharp contrast to how the corporate tax system works, where residency is everything. For instance, a company is deemed a resident if its central management and control is here, and non-resident companies only pay tax on income sourced in Australia. You can explore more about Australian corporate tax highlights to see just how different those rules are.

Your Guide to ATO Compliance and Record Keeping

When it comes to handling foreign income tax in Australia, there's one golden rule: being proactive isn't just a good idea, it's your best strategy. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) isn't what it used to be. It now runs sophisticated data-matching programs, swapping information with tax authorities all over the globe.

This means the old approach of hoping your foreign income or assets slip under the radar is not just risky—it's completely outdated. Getting it right from the start is about more than just avoiding trouble; it’s about making sure you meet your obligations correctly and aren’t paying a dollar more than you need to.

The Importance of Detailed Records

Think of meticulous record-keeping as the foundation of your tax return. It’s absolutely non-negotiable. Without solid proof, you can't accurately calculate your income, and you certainly can't claim valuable offsets like the FITO. Your records are the evidence that backs up every number you declare to the ATO.

For every stream of foreign income, you need a clear paper trail. This includes:

Proof of Income: This could be foreign employment contracts, payslips, or any statement showing the gross income you received.

Tax Payment Evidence: Keep official tax assessments from foreign governments, receipts showing tax you've paid, or bank statements that detail the exact payment.

Transaction Statements: These are your records from foreign banks or investment platforms, detailing any interest, dividends, or capital gains.

Having these documents organised is the key to a stress-free tax time. For a deeper dive, check out our [guide on tax record keeping essentials](https://www.baronaccounting.com/post/tax-record-keeping-kr), which breaks down what to keep and for how long.

Currency Conversion and Reporting

Every dollar of foreign income must be converted into Australian dollars (AUD) before it lands on your tax return. The ATO gives you two main options: you can use the specific exchange rate on the day of each transaction, or you can use an average rate over a certain period.

The most important thing here is consistency. Whichever method you choose, you need to stick with it for the financial year.

The consequences for getting this wrong can be steep, ranging from significant financial penalties to hefty interest charges on unpaid tax. The ATO is firm on compliance, which makes accurate and timely reporting your most effective line of defence.

This focus on compliance isn’t just about income. The government is also tightening rules around foreign investment. A key example is the ban on foreign persons purchasing established dwellings from 1 April 2025, a move designed to free up housing supply for Australians. The ATO has even received specific funding to enforce these rules, showing just how serious the government is about maintaining a fair system. You can learn more about these federal budget tax measures at Ashurst.com.

Where to From Here? Getting the Right Support for foreign income tax Australia

Navigating the world of foreign income tax can feel like you're trying to solve a puzzle with missing pieces. It's complex, and the stakes are high. But the best path forward is always to take clear, confident steps. Getting every detail right isn’t just about staying on the right side of the ATO; it’s about making sure you claim every single offset and deduction you’re entitled to.

Don't leave your financial outcome to guesswork. If you're looking for practical ways to improve your situation, our guide on how to maximise your tax return in Australia is a great place to start. For advice tailored specifically to your circumstances, our team is always here to help.

Your peace of mind is what matters most. Getting professional advice takes the guesswork out of reporting global income, ensuring you meet all your obligations while making your money work smarter for you. You don’t have to tackle foreign income tax alone—expert support is just a conversation away.

Your Top Questions About Foreign Income, Answered

Working through the rules for foreign income tax in Australia can feel a bit tricky. When you're trying to get your tax return just right, it’s natural for questions to pop up. Here are the answers to the most common queries we hear from our clients.

Do I Have to Declare Foreign Income if I Already Paid Tax on It Overseas?

Yes, you absolutely do. This is one of the most important rules to get your head around. If you’re an Australian resident for tax purposes, you need to tell the ATO about all your income from around the world, even if a foreign government has already taken a slice.

But don't worry, this doesn't mean you'll be taxed twice. Australia has a system to prevent that, called the Foreign Income Tax Offset (FITO).

Think of FITO as a credit for the tax you've already paid overseas. The ATO acknowledges what you’ve paid abroad and reduces your Australian tax bill on that same income accordingly. It’s their way of making sure you’re not out of pocket.

What Happens if I Forget to Declare My Foreign Income?

Forgetting to declare foreign income can lead to some pretty serious headaches, including penalties and interest charges from the ATO. Thanks to powerful data-matching agreements with tax authorities worldwide, it's not a matter of if they'll find out, but when.

If you suddenly realise you've made a mistake or left something out on a previous tax return, the best thing you can do is make a voluntary disclosure. Coming forward to fix the error before the ATO contacts you almost always results in much lower penalties. It shows you’re trying to do the right thing, and they look at that much more kindly than if they have to chase you down.

How Do I Convert My Foreign Income to Australian Dollars?

All your foreign income must be converted and reported in Australian dollars (AUD) on your tax return. The ATO gives you two main ways to do this:

The Specific Rate Method: This involves converting each payment using the exact exchange rate on the day you received it. It's precise but can be a bit more work.

The Average Rate Method: This is often the simpler choice. For regular income streams, you can use an average exchange rate for the entire financial year. The ATO helpfully publishes these average rates, saving you a lot of time.

You'll need to be consistent with the method you choose for each income source. The most important thing is to keep clear records of how you did your conversions in case the ATO asks.

• Need assistance? We offer free online consultations: – Phone: 1800 087 213 – LINE: barontax – WhatsApp: 0490 925 969 – Email: info@baronaccounting.com – Or use the live chat on our website at www.baronaccounting.com

📌 Curious about your tax refund? Try our free calculator: 👉 www.baronaccounting.com/tax-estimate

For more resources and expert tax insights, visit our homepage: 🌐 www.baronaccounting.com

Comments