Ultimate Guide to Capital Gains Tax Calculation Australia

- Jul 4, 2025

- 15 min read

At its heart, the capital gains tax (CGT) calculation in Australia is pretty straightforward: you simply subtract an asset's cost base from its sale price. The resulting profit, or "capital gain," is then tacked onto your assessable income for the financial year.

One of the biggest factors in play here is the 50% CGT discount. If you've held onto an asset for more than 12 months, this handy little rule lets you slice your taxable gain in half. It’s a real game-changer.

Decoding Capital Gains Tax Calculation in Australia

First things first, Capital Gains Tax (CGT) isn't a separate, standalone tax. It’s actually a component of your regular income tax. You'll only have to deal with it when a ‘CGT event’ happens, which, for most of us, is when we sell an asset. Getting this basic concept right is the first step to managing your tax affairs properly.

CGT itself isn't new—it was introduced way back on 20 September 1985. The system we use today, however, was shaped by a major policy shift in 1999 that brought in the 50% CGT discount. The whole idea was to encourage people to invest for the long term, and it’s a core part of the landscape we navigate now.

What Is a CGT Asset?

When people hear "CGT," they usually think of property and shares. But the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) has a much broader definition. It's crucial to know what counts as a CGT asset so you don't get caught out missing a potential gain or loss.

Here are the usual suspects:

Real estate: This includes investment properties, holiday homes, and even vacant land.

Shares and similar investments: Think stocks in listed companies or units in managed funds.

Cryptocurrency: Digital currencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum are treated as property for CGT purposes.

Collectables: Things like artwork, jewellery, or antiques, but only if you paid more than $500 for them.

Personal use assets: These are items for your own enjoyment, like a boat or fancy furniture, if you acquired them for over $10,000.

The Main Residence Exemption

This is probably the most well-known—and most valuable—CGT exemption out there. In most situations, when you sell your family home (the one you actually live in), you won't pay a cent of CGT on the profit. It’s a huge relief for homeowners.

But, and this is a big but, the rules can get tricky. For instance, if you’ve used part of your home to earn an income—maybe by renting out a spare room or running your business from a home office—you might only get a partial exemption. This is a detail many people miss, and it can have a massive impact on your tax bill.

For anyone in this boat, we've put together a detailed guide on how [capital gains and rental property rules interact](https://www.baronaccounting.com/post/capital-gains-and-rental-property).

Key Takeaway: The main residence exemption is fantastic, but it's not a free-for-all. Any income-producing activity from your home will likely trigger a partial CGT liability when you sell. That’s why keeping meticulous records from day one is absolutely essential.

To help you get a quick handle on these concepts, here’s a simple table breaking down the essentials.

Key CGT Concepts at a Glance

Concept | Brief Explanation | Why It's Important |

|---|---|---|

CGT Asset | Any form of property or a legal or equitable right, including real estate, shares, crypto, and certain valuables. | You need to correctly identify what an asset is to know if a CGT event has even occurred. |

CGT Event | The trigger for a potential capital gain or loss, most commonly the sale or disposal of an asset. | This is the moment your CGT obligation is created. Knowing the date is critical for reporting in the right financial year. |

Cost Base | The total cost of acquiring, holding, and disposing of an asset, including purchase price and associated fees. | A higher, accurately calculated cost base directly reduces your capital gain, which means less tax to pay. |

Capital Proceeds | The money or property you receive when a CGT event happens. | This is the starting point for your calculation. It's not just the sale price; it can include other forms of compensation. |

CGT Discount | A 50% reduction on the capital gain for assets held for more than 12 months by individuals and trusts. | This is one of the most significant tax-saving tools for long-term investors. Missing out can be a costly mistake. |

Main Residence Exemption | A full or partial exemption from CGT on the sale of your primary home. | Potentially the most valuable CGT exemption available, but its rules can be complex, especially if you've used your home to earn income. |

Understanding these building blocks is the foundation for successfully navigating your CGT obligations and making sure you're not paying a dollar more in tax than you need to.

Building Your Asset's Cost Base Correctly

When it comes to capital gains tax in Australia, the secret isn't just about the sale price—it's about understanding what the asset truly cost you. A well-calculated cost base is your best friend for legally minimising your tax bill. So many investors make the mistake of thinking the cost base is just the purchase price. That single assumption can leave thousands of dollars in legitimate expenses on the table.

Your cost base is essentially the total value you've given up for an asset, plus a whole range of related costs. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) actually breaks this down into five key elements. Getting this right from the start is a financial strategy, not just good bookkeeping.

The Five Elements of Your Cost Base

Think of your cost base as the complete financial story of your asset. The ATO lets you build this story using costs from five distinct categories, each one crucial for painting a full picture of your investment.

These five elements are:

Money or property given for the asset: This one's the most obvious – it’s the initial price you paid.

Incidental costs of acquiring the asset or CGT event: These are the direct costs of both buying and selling.

Costs of owning the asset: These are specific holding costs you haven't already claimed as a tax deduction.

Capital costs to increase the asset’s value: This covers major improvements, not just general repairs and maintenance.

Capital costs to preserve or defend your title: Think legal fees to protect your ownership rights.

Digging Deeper Into Incidental Costs

This is where most people have their first "aha!" moment. Incidental costs are all those necessary expenses you paid to make the purchase or sale happen. They add up quickly.

Let's say you bought an investment property for $600,000. Your incidental buying costs might look something like this:

Stamp duty: $25,000

Conveyancing/legal fees: $2,500

Borrowing expenses (like loan application fees): $800

A valuation fee you needed for the purchase: $500

Just like that, you’ve added $28,800 to your initial purchase price. Your starting cost base is now $628,800 before anything else. The same logic applies when you sell. Factoring in all eligible expenses is key, and that includes the direct costs of the sale. For example, understanding various selling fees and commissions ensures you don't miss adding things like agent commissions and advertising fees to your cost base.

Including Ownership and Improvement Costs

For an asset like a rental property, you can sometimes include holding costs in your cost base, but only if you haven't already claimed them as a tax deduction against your rental income. This typically includes things like council rates, land tax, insurance, and the interest on your loan. This rule is especially helpful for vacant land that isn't earning you any income.

Capital improvements are the other big one. These need to be genuine enhancements that add real, lasting value—not just routine maintenance to keep the place ticking over.

Scenario: Imagine you bought an investment property a decade ago. Five years into owning it, you spent $50,000 on a massive kitchen and bathroom renovation. That's not a simple repair; it's a significant capital improvement. You can add that entire $50,000 to your cost base, which will make a huge difference in reducing your capital gain when you eventually sell.

By diligently tracking every single eligible expense across these five elements, you're not just being compliant. You're being smart and strategically optimising your tax outcome.

Choosing the Right CGT Calculation Method

Once you've figured out your net capital gain, the next move is a strategic one: picking the best calculation method. This isn't a one-size-fits-all decision. The method you choose can seriously change your final tax bill, so understanding your options is crucial to make sure you don't pay a cent more than you have to.

The Australian tax system gives you a few different ways to work out your capital gain. Your eligibility for each method really comes down to things like how long you've owned the asset and when you bought it. The goal is always the same: choose the method that gives you the lowest possible capital gain to add to your taxable income.

The Popular 50% CGT Discount Method

For most everyday investors, the discount method is the go-to and usually the most beneficial. It's pretty straightforward. If you're an individual, a complying super fund, or a trust, and you've held onto a CGT asset for at least 12 months before selling it, you can slash your capital gain by 50%.

This is a powerful discount that effectively halves the profit that gets taxed. Let's say you made a $50,000 capital gain on some shares you held for 18 months. You can apply the discount, which means only $25,000 gets added to your assessable income for the year. Simple. Keep in mind, though, that companies can't use this discount.

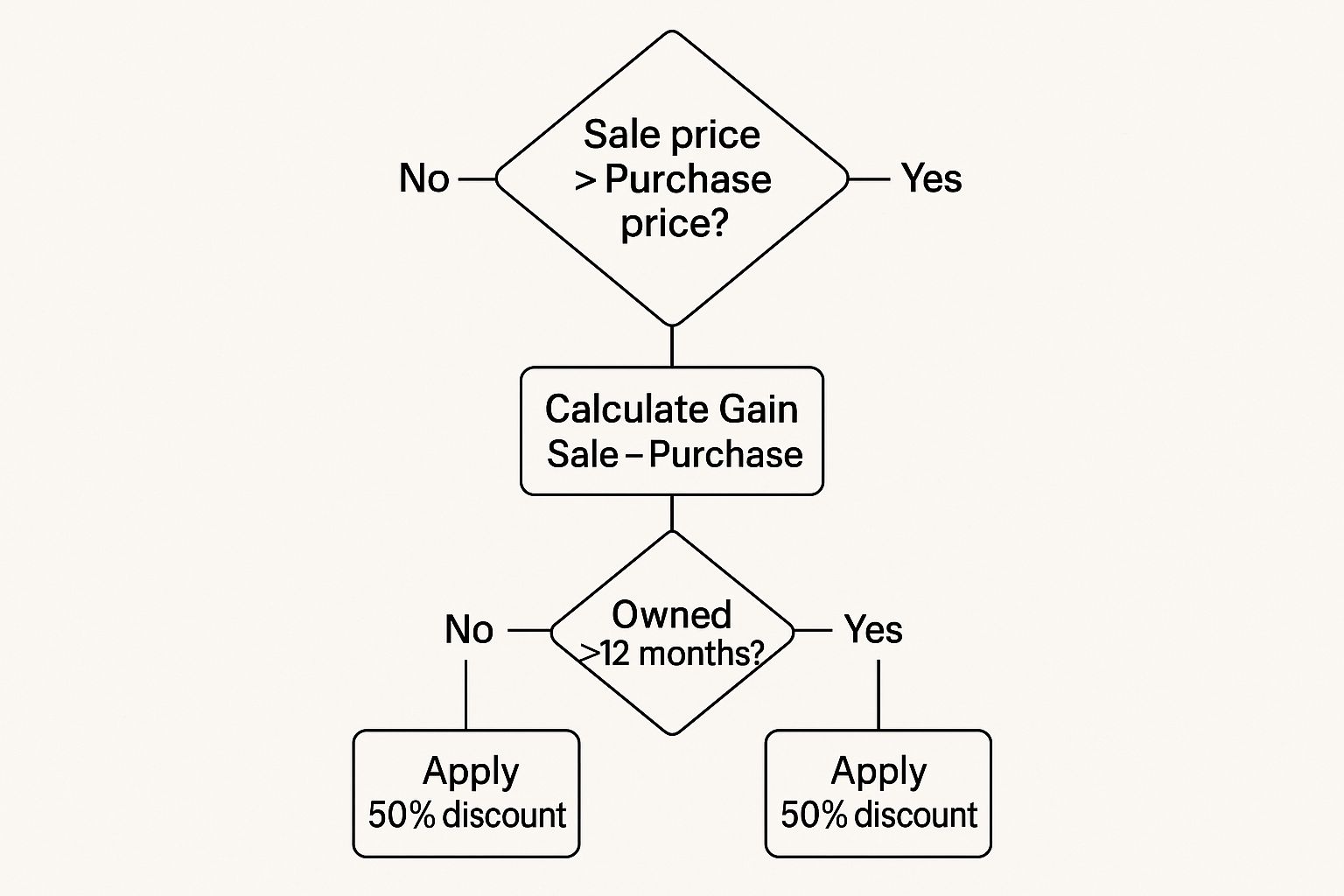

This decision tree gives you a quick visual to check if the discount method might be for you.

As the infographic makes clear, that 12-month ownership period is the magic number for unlocking the 50% CGT discount.

The Indexation Method For Older Assets

Got an asset you acquired before 21 September 1999? You might have another option: the indexation method. This method lets you increase your cost base to account for inflation up until that 1999 date, which helps to shrink your capital gain.

You calculate this by applying a specific Consumer Price Index (CPI) factor to the different elements of your cost base. The ATO has all the historical indexation factors you'll need. The catch? Indexation was frozen on 30 September 1999, so you can't factor in any inflation that happened after that date.

Important Note: You can't have your cake and eat it too. You cannot use both the indexation method and the 50% discount method on the same capital gain. If you're eligible for both, you have to pick one.

Making the Strategic Choice

So, how do you decide? If you bought an asset before September 1999 and held it for over a year, you’ll need to do the maths for both methods. Calculate the gain using the indexation method, then calculate it again using the discount method. Whichever gives you the smaller taxable amount is the winner.

For assets bought between late 1985 and late 1999, you have this unique choice between adjusting for inflation or just halving the gain. Sometimes, especially if there was high inflation while you held the asset before 1999, the indexation method could give you a better result than the 50% discount. For instance, a worked example might show an indexed gain of $1,000 versus a discounted gain of $1,750, proving it really depends on the specifics. To dig deeper into how these rules came about, you can explore the history of capital gains tax in Australia.

If you bought the asset after 21 September 1999, the choice is simple. The only method available to reduce your gain is the 50% discount, as long as you’ve held it for more than 12 months. And for any assets you've held for less than a year, neither the discount nor indexation applies—the entire capital gain gets added to your income.

Using Capital Losses and Exemptions to Your Advantage

Calculating your capital gains tax in Australia isn't just about crunching numbers. It’s about being smart and using every tool the tax system gives you. If you understand how to properly apply capital losses and exemptions, you can dramatically cut your final tax bill, turning what could be a big headache into something far more manageable.

A core rule you absolutely need to get right is that capital losses can only be used to offset capital gains. You can't, for example, use a loss from selling shares to lower the tax on your regular salary or business income. This is a fundamental principle of the CGT framework.

If you’ve had a mix of wins and losses in the same financial year, you must subtract your current-year capital losses from your current-year capital gains first. This has to be done before you even think about applying any CGT discount.

What to Do with Capital Losses

So, what happens if your losses for the year are bigger than your gains? That leftover amount is called a net capital loss, and the good news is, it’s not wasted. You can carry it forward indefinitely to use against capital gains in future years.

There's no time limit on this. The loss just sits on your tax record, waiting for the next time you realise a capital gain.

Key Insight: When you do have a capital gain in a future year, you must apply any carried-forward net capital losses from previous years before you apply the 50% CGT discount. This order is non-negotiable and ensures you get the most value out of your losses.

The Main Residence Exemption: Your Most Powerful Tool

For most Australian homeowners, the main residence exemption is easily the most significant CGT concession out there. In simple terms, it means you pay no capital gains tax when you sell your family home. But as with most things in tax, the devil is in the details.

The full exemption only works if the property was your main home for the entire period you owned it and you didn't use it to earn income. The moment you start renting out a spare room or running a business from the property, you can trigger a partial CGT liability.

The rules here can get tricky, especially when life throws a curveball. That’s where things like the "six-year rule" become incredibly useful, allowing you to treat a property as your main residence for up to six years after moving out, as long as you don't claim another property as your main home. To get across all the crucial details, it's worth reading our complete guide on the [CGT exemption for your main residence](https://www.baronaccounting.com/post/cgt-exemption-main-residence).

Other Key Exemptions and Concessions

Beyond your family home, there are several other situations that can help reduce or even wipe out your CGT bill.

Small Business CGT Concessions: If you're a small business owner selling an active business asset, you might be eligible for one of four major concessions. These can slash or even completely eliminate the capital gain.

Inherited Assets: How CGT applies to inherited assets is unique. Generally, if the deceased bought the asset before 20 September 1985, you are exempt from CGT when you sell it. If they bought it after that date, your cost base is typically its market value at the date of their death.

A Real-World Walkthrough of a CGT Calculation

Theory is great, but nothing makes the rules click quite like seeing a capital gains tax calculation in Australia play out from start to finish. Let's walk through a realistic scenario with an investment property to see how all these moving parts work together in practice.

Meet Alex, an investor who's just sold his rental property. Now comes the fun part: figuring out his CGT liability.

Building the Cost Base

The first—and arguably most important—job is to nail down the cost base. This isn't just the price Alex paid for the property. A smart investor knows to track down every single eligible expense to build up that cost base, which directly reduces the taxable gain later on.

Here’s what Alex has on his list:

Initial Purchase Price (in 2016): $500,000

Stamp Duty on Purchase: $20,000

Legal Fees for Purchase: $2,000

Major Renovation (new deck in 2019): $15,000

Real Estate Agent Commission on Sale: $18,000

Legal Fees for Sale: $2,500

Adding it all up, Alex’s total cost base comes to: $500,000 + $20,000 + $2,000 + $15,000 + $18,000 + $2,500 = $557,500

A quick but vital note: Alex can't include costs he's already claimed as annual tax deductions, like his mortgage interest or council rates. That would be double-dipping. However, if you've made capital improvements, remember to also factor in related write-offs, like [claiming depreciation on investment property](https://www.baronaccounting.com/post/depreciation-on-investment-property) for any new assets installed.

Calculating the Gross Capital Gain

Next up are the capital proceeds. It's a straightforward number—the sale price. Alex sold the property for $800,000.

To get his gross capital gain, he just subtracts the cost base from his sale price: $800,000 (Capital Proceeds) - $557,500 (Cost Base) = $242,500 (Gross Capital Gain)

Applying Capital Losses and the CGT Discount

Before Alex gets too excited, he remembers a loose end from a few years back: a carried-forward capital loss of $10,000 from a bad run on the stock market. The ATO is very clear that he must use this loss to reduce his gain before he thinks about any discounts.

Gross Capital Gain: $242,500

Less Capital Loss: -$10,000

Net Capital Gain: $232,500

Crucial Order of Operations: Always subtract capital losses from your capital gain first. Applying the discount before the loss is a common error that leads to paying more tax than necessary.

Now for the good news. Since Alex owned the property for well over 12 months (from 2016 to now), he qualifies for the 50% CGT discount. He applies this to his net capital gain.

$232,500 (Net Capital Gain) x 50% = $116,250

This final figure, $116,250, is Alex’s taxable capital gain. It’s not a separate tax bill. Instead, he’ll add this amount to his other income for the financial year (like his salary), and the total will be taxed at his marginal tax rate.

Common CGT Questions Answered

Even once you've got your head around the basics of capital gains, real-life situations can throw a spanner in the works. Let's walk through some of the questions we hear all the time from clients, clearing up the confusion around these tricky scenarios.

What Happens if I Sell an Inherited Asset?

When it comes to inherited assets, the CGT rules all hinge on a key date: 20 September 1985.

If the person who left you the asset bought it before this date (when CGT was first introduced), you're generally in the clear. You won't have to pay any CGT when you eventually sell it.

However, if they acquired it on or after this date, things are different. The asset's 'cost base' for you is its market value on the date of their death. This is the figure you'll use to calculate your capital gain or loss, not what they originally paid for it. This area can get particularly complex, especially if the asset was their main home, so getting professional advice is always a smart move.

How Is Capital Gains Tax Calculated on Cryptocurrency?

The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) is very clear: cryptocurrency is a CGT asset, not currency. This means any time you "dispose" of it, you trigger a CGT event.

So, what counts as disposing of crypto?

Selling it for Aussie dollars.

Swapping it for another type of crypto (e.g., Bitcoin for Ethereum).

Using it to buy something, like a coffee or a new laptop.

The calculation itself is the same as for any other asset: Capital Proceeds minus its Cost Base. Remember to include the purchase price and any transaction or "gas" fees in your cost base. And yes, if you've held the crypto for more than 12 months, you might be eligible for the 50% CGT discount. Keeping meticulous records of every single transaction is absolutely non-negotiable.

Key Takeaway: Don't fall into the common trap of thinking CGT only matters when you cash out to Australian dollars. Every single trade is a taxable event. Documenting each transaction the moment it happens will save you a massive headache later on.

Can I Claim the Full Main Residence Exemption if I Earned Income From My Home?

Probably not, but you can likely claim a partial exemption. If you've used a part of your home to earn income—whether that's renting out a room or running a business from a home office—you'll need to work out the taxable portion of your capital gain.

This is typically calculated based on two factors: the floor area you used for the business and the length of time you used it for that purpose. It's crucial to get this right and have all your records in order. To make sure you're not missing anything, our comprehensive [tax return checklist](https://www.baronaccounting.com/post/tax-return-checklist) is a great place to start.

Feeling Overwhelmed by CGT? Let's Sort It Out.

Working through Australia's capital gains tax rules can feel like a maze. From piecing together every element of your cost base to picking the right calculation method, it demands serious attention to detail. While you can definitely tackle it yourself, the complexities can be a real headache. Even a small oversight could mean you end up with a much larger tax bill than you needed to.

This is exactly where getting a professional eye on things makes all the difference. An expert will make sure every single eligible deduction and concession is applied correctly, which could genuinely save you thousands. If you're managing complex finances, it’s also useful to know what tools the pros use.

Bringing in professional support isn't just about minimising your tax bill. It's about the peace of mind that comes from knowing your financial affairs are not only compliant but fully optimised.

Why struggle with the complexities of CGT alone? Our experienced team is here to help you get the best possible outcome.

• Need assistance? We offer free online consultations: – Phone: 1800 087 213 – LINE: barontax – WhatsApp: 0490 925 969 – Email: info@baronaccounting.com – Or use the live chat on our website at www.baronaccounting.com

📌 Curious about your tax refund? Try our free calculator: 👉 www.baronaccounting.com/tax-estimate

For more resources and expert tax insights, visit our homepage: 🌐 www.baronaccounting.com

Comments